Gleick 2013 Accuracy, precision, and significance

By Peter Gleick on February 13, 2013.

We’re bombarded with numbers every day. But seeing a number and understanding it are two different things. Far too often, the true “significance” of a figure is hidden, unknown, or misjudged. I will be returning to that theme often in these blog posts in the context of water, climate change, energy, and more. In particular, there is an important distinction between accuracy and precision.

Here is one example – reported cases of cholera worldwide. Cholera is perhaps the most widespread and serious water-related disease, directly associated with the failure to provide safe drinking water and adequate sanitation. Billions of people lack this basic human right and suffer from illness as a result. Millions die unnecessary deaths.

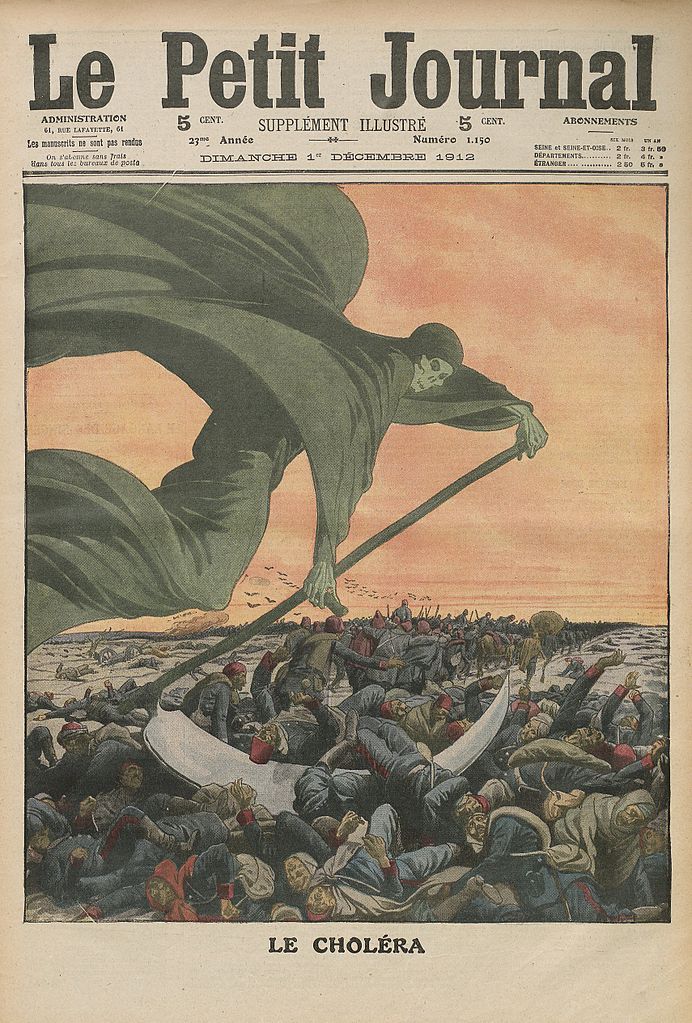

The scourge of cholera. December 1912. Le Petit Journal, Bibliothèque nationale de France. [This image is in the public domain.]

The scourge of cholera. December 1912. Le Petit Journal, Bibliothèque nationale de France. [This image is in the public domain.]

The World Health Organization has reported that in 2011 (the last year for which comprehensive data are available) 58 countries reported 589,854 cases of cholera.

OK, I see that number, but what does it mean? Is it accurate? Is it precise?

Accuracy and precision are not the same things. In the field of science and data, “accuracy” is typically considered to be a measure of how close a number is to that quantity’s true value.

“Precision” is a term with two relevant meanings. The first describes the degree to which repeated efforts to do, or measure, something will produce the same results. The second meaning is a measure of the relative accuracy with which any given number can be represented, and is typically expressed through the use of “significant figures.”

Take, for example, the number 123. This has three significant figures. The implication is that the actual number is not 122 or 124, but 123 precisely, with a margin of error of a half of the last place (in this case 0.5). If the actual precision of measurement is not this small, then perhaps this number should be represented as 120 (with two significant figures), or even 100 (with only one significant figure).

(A minor aside: the number 100 could have 1, 2, or 3 significant figures – we don’t know unless it is stated explicitly. One way to do this is to use decimal notation. The number 100. (with the decimal point) has three significant figures, and can also be expressed as 1.00 x 102.)

Any particular data can be accurate, precise, both, or neither.

So, back to cholera. This number of cases -- 589,854 -- seems very precise. It is reported to six significant figures – a very high degree of precision.

In fact, however, this number is an example of “false precision” – it is presented in a way (with six significant figures) that implies, incorrectly, a higher degree of both precision and accuracy than reality warrants.

Why? First, it is entirely possible that this number is exactly the sum (i.e., it is precise) of the number of cases of cholera reported to WHO by the 58 reporting countries. But experts on water-related disease note the following:

- Many countries around the world do not report water-related diseases at all. As noted above, in 2011 only 58 countries reported cholera. We know cholera occurred in countries not reporting.

- Most cholera outbreaks are not detected. Thus, even countries reporting cholera underreport.

- There is no agreed-upon standard definition for determining if a case of extreme or acute watery diarrhea is “cholera” or a different illness that presents the same way.

- Health surveillance systems (i.e., medical systems for tracking, recording, and reporting disease) vary dramatically from country to country in their quality and completeness.

- Some major countries, known to have extensive and severe cholera outbreaks, typically report zero instances of cholera because they either fear the stigma associated with the failing to provide adequate water systems or they hide cholera cases by labeling them as something else (such as acute watery diarrhea).

Thus, this highly precise number is neither precise nor accurate. Indeed, it is grossly inaccurate. The WHO acknowledges this, and indeed, believes the officially reported cases could represent only a small fraction of the actual number that occurs. Taking these uncertainties into account, WHO estimates that there are as many as 10 times more cases than are actually reported. A more detailed statistical analysis recently suggested that overall there are around 2.8 million cases of cholera every year (with an uncertainty range of 1.2 to 4.3 million) and about 91,000 deaths (with an uncertainty range of 28,000 to 140,000).

So, beware misleading numbers. The officially reported estimates of cholera cases are neither precise (despite six significant figures), nor accurate.

Finally, there is another aspect to “significance.” That is the importance of the figure in some context. In this sense, the cholera numbers may be neither accurate nor precise, but they are significant. They tell the story of a horrible and unnecessary situation – a deadly, crippling, and preventable disease that is the result of our failure to provide safe water and sanitation to all the population on the planet. Cholera is completely preventable – we've effectively eliminated it in the United States and other industrialized countries by putting in place wastewater treatment and water purification systems. Let’s improve our data collection and reporting system, so we know, accurately, the extent of the problem, and then let’s move quickly to do what is necessary to reduce and eliminate cholera.

Link: Accuracy, precision, and significance: The misery of cholera