The Work Group Within the Organization: A Sociopsychological Approach

Peter M. Newton and Daniel J. Levinson Department of Psychiatry, Yale University Medical School PSYCHIATRY, Vol. 36, May 1973, pp. 115-142.

Citation: Newton, P. M., & Levinson, D. J. (1973). The work group within the organization: A sociopsychological approach. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes, 36(2), 115–142. Link (paywalled): https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1973.11023751

(Excerpts formatted by Bill Anderson, 2021-04-19. Note: footnote numberings are unique to this extract; they do not match the numbering in the full article.)

Abstract

THE SMALL WORK GROUP is a basic component of modern organizational life. Crucial tasks at every level of the organization are entrusted to work groups of various kinds: executive committees, staff meetings and committees with responsibility for policy review, budget planning, training, integration of services, and the like. Work groups abound in the clinical facility and university as in the business firm and government agency. The work group is an important linking device between the organization and the individual. From the point of view of the organization, it serves as a mechanism to accomplish or to undermine diverse organizational goals. From the point of view of the individual the work group is a significant arena in which he(sic) can learn about the organization and have a voice in the shaping of its policies and practices -- or in which he can experience the corruption of theˆ organization and his own powerlessness within it. By and large, work groups do not work very well; they do little either to accomplish organizational tasks or to elicit the responsible, constructive participation of individual members. The resultant costs to both the organization and the individual members are enormous. Despite the widespread dissatisfaction with work groups, relatively little effort has been given to the systematic analysis and improvement of their functioning. In this paper we present a theoretical approach and demonstrate its utility in the analysis of a clinical team within a psychiatric research ward.

Introductory

A work group is ordinarily established in order to carry out one or more organizational tasks. The task is given at least preliminary definition in advance and is indicated in the group's title (e.g., the program committee or the ... leadership meeting), but it may be clarified, expanded, or markedly changed as the group evolves. Membership in the group may be based on assignment, election, or volunteering. Our emphasis here is on the small work group, which contains at the most 20 members and usually under 15. Most work groups are within this range of size.

AIMS AND THEORETICAL APPROACH

Our primary purpose, as noted above, is to develop a theoretical framework for the analysis of the work group.(Note1) The major rubrics in this framework are: task, social structure, culture, and social process. As used here, these terms refer not to simple, unitary concepts but to complex, interrelated perspectives or vantage points from which groups and organizations can be examined.

The concept of task refers to the end toward which work is directed; the work is successful to the extent that it accomplishes the task. The conceptual emphasis upon task serves to keep in focus the raison d’étre of the group: the ongoing work, and indeed the very existence of the group, derive from the organization which has created it as a means toward some larger goals. The notion of task would seem to be rather concrete and self-evident, and hardly meriting a major place in a theoretical scheme. In the simplest case, a group has a single, stable, well-defined and consensually agreed-upon task that it pursues unswervingly to completion.

The simplest case is, however, much more the exception than the rule. By and large, the definition and implementation of task is a complicated matter for the group, and the analysis of task-evolution poses difficult problems for the investigator. Rather than having a single primary task the group may have multiple major tasks without a clear order of priority; in this case a great deal of effort may go (explicitly or implicitly) to the clarification of task priorities or to struggles over the ordering of priorities. Again, although it may be possible to define a single task simply and concretely on paper, complications may arise over the meaning of key terms in the task-definition or over the nature and priority of the component tasks that were not clearly recognized in advance. Even where tasks are clearly defined and their respective priorities established, the group or the organization may find that there are serious incompatibilities among the major tasks to which it has become committed.

One manifestation of the multiplicities, ambiguities, and contradictions relating to task-definition is the consternation that is usually evoked in a group when, in the midst of a silence or a heated argument, a member suddenly asks, “Could someone tell me the real purpose for which this group is meeting?” Tasks have a way of shifting, multiplying, dissolving, appearing different to different group members. Most groups spend a good deal of time in dealing with (or in avoiding) problems of ambiguity or contradiction in task-definition, problems of establishing an order of task-priorities, and problems of dissensus in these matters. In our view, then, the analysis of task-definition and its vicissitudes deserves major attention in the study of the work group.

The work group must also be examined from the perspective of its evolving social structure. Our emphasis here will be on two components of structure, namely the division of labor and the division of authority. There is a division of labor to the extent that different members carry out different parts of the total work of the group. This differentiation is ordinarily but not always expressed in the naming of positions within the group (e.g., in terms of the clinical example in this paper: teachers, students; chairman, members representing different constituencies; ward chief, head nurse, and others comprising a ward leadership group). Informal, implicitly defined positions may also emerge (e.g., it is “understood” that Member X functions as assistant to the chief, or that Member Y attends meetings but does no work). There is a division of authority to the extent that the legitimate power and responsibility to make decisions are distributed unequally within the group.

At least a minimal degree of hierarchy exists in every organizational work group but - especially in mental health and related professional organizations - the lines of authority are often blurred and made covert. The social structure of the work group tends to reflect the social structure of the organization. The individual members are often appointed to represent their occupations or work units. The hierarchy in the work group ordinarily corresponds to the hierarchy in the organization; thus, the chairman of a committee usually has higher organizational status than any other committee member, and members having low organizational status have a hard time functioning as peers with high-status members even when no formal distinctions are made.

The work group tends also to develop a culture, that is, a relatively enduring pattern of core values, assumptions, and beliefs that provides a framework for group development and action. As in the case of social structure, the culture of the work group is strongly influenced by the culture of the organization. To the extent that the organization has an integrated, well-established culture, the work group is likely to form a similar, derivative culture. In times of ferment and social conflict, the organization contains not only a traditional culture but in addition one or more newly emerging and competing cultures. Analysis of the organization, and of the work group, must therefore take into account the struggles among conflicting cultural values and orientations.

Finally, we examine the work group from the vantage point of social process. We use this term in the broad sense to refer to how a group works — to its modes of functioning, the ways in which it goes about accomplishing or avoiding or sabotaging its tasks. Social process thus has myriad aspects, from the highly rational forms of planning, problem solving, and collaborative use of technical skills to the most irrational forms of destruction of any real work as well as exploitation and humiliation of members. Our analysis of social process will focus especially on recurring themes in the ongoing life of the work group. The themes derive both from the situational realities and from the widely shared feelings, fantasies, and conflicts of individual members. Once again, work group and organization are interrelated: the process themes in the organization tend to be reflected in its component groups.

PRIMARY TASK

A task is the end toward which work is aimed. That is, we differentiate modes of work from task. There are often various kinds of work which seem more or less appropriate for a given group to engage in (e.g., in a colloquium meeting, to have each member lecture, to bring in outside speakers, to create panels for discussion, etc.). However, a rational and effective choice among various modes of work can only be made by reference to the group’s task, that is, by reference to the end toward which the work is aimed. The work which the group engages in needs to be directly and necessarily related to the task being pursued. Where it is not, the enterprise and, ultimately, the group, may be in jeopardy.

Organizations usually, and groups at times, have multiple major tasks. Following Miller and Rice, we define the primary task as the task which the group or organization must achieve at some significant level if it is to survive. Typically, other tasks are given second priority, and resources such as time, energy, space, and money are allocated accordingly. Often the secondary tasks will stand in a support or maintenance relationship to the primary task -- for example, the recruitment of faculty in a teaching institution.

The definition of primary task has important consequences for a group or organization. As noted above, it may provide the basis for decisions regarding the mode of work the group will adopt and the technology it will employ. Definition of primary task may also form the basis for the creation of social structures aimed at organizing work on the task. Finally, it provides an essential criterion for evaluating performance.

Definition of primary task also generates conflict, stimulating the emergence of competing values, ideologies, and factions. Put simply, as soon as people know what it is that they are supposed to do, serious differences may emerge as to how best to do it, whether it is worth doing, and whether some other task would not be more valuable.(Note3)

As noted earlier, the definition of primary task and the relative priority of the major tasks are often ambiguous or nonconsensual. Moreover, the “official” task of a group may differ from what is widely understood to be the real task. Such ambiguity regarding task definition has major consequences. If there is unclarity in a system about what it is that its members are to do, then competing and incompatible goals may be variously pursued and the legitimacy of any given action is in doubt.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

For present purposes, we limit our discussion to two critical aspects of social structure, namely, the relatively enduring arrangements which govern (1) the division of labor and (2) the division of authority and the boundaries which are created by these divisions. We shall consider each element separately.

The Division of Labor

The division of labor refers to the way in which the total work of a social system is distributed among its component parts. This division is formalized in the creation of positions. Positions are the basic element of the division of labor in groups and organizations. They are, more or less, formally defined and permanent; they are changed through a redefinition of organizational structure, not through the comings and goings of individuals. Individuals occupy positions and from these positions engage in activities or carry out functions -- that is, they define and take roles.(Note8) Role performance is structurally based in requirements which accompany a given position. However, the requirements are typically ambiguous enough and the role standardizing forces within the social system are weak enough so that individual role performance is shaped not only by formal requirements (and situational exigencies) but also by the personal attributes of the individual who occupies the position.

The greater the differentiation of subsystems and individual labor, the greater is the need for integration of individual and group activities. If integration is to be achieved, one or a few individuals must have responsibility for ordering and coordinating the activities of many others. Responsibility requires that one have the authority -— the legitimate right—to make demands, exert influence, and impose sanctions. Organizations are stratified in order to achieve the integration necessary to the fulfillment of complex tasks; that is to say, the positions comprising the social structure of the organization are hierarchically arranged. This hierarchy constitutes the division of authority which is another central aspect of social structure.

The Division of Authority

We refer here to the patterning of subordination within the organization. Authority confers legitimacy, or right, to initiate and influence processes, to command and direct resources.(Note7) Within a rational work structure, authority is vested in positions not in individuals, and authority is a corollary of responsibility. That is, a position is invested with the authority necessary to meet the responsibilities corresponding to the level of that position within the organizational hierarchy. If the occupant of a position is responsible for supervising and coordinating the work of a number of individuals, then he should have available to him as a property of his position sufficient authority to cause subordinates to be responsive to his directions or suggestions. It is empirically true, of course, that often a position carries far greater responsibility than authority. In such instances, some degree of disorganization is the predictable result and task performance suffers accordingly.

It is useful to distinguish between the authority which, as a structural property, is inherent in a position and the authority which the occupant of that position in fact exercises. The latter may be greater or less than the former. The individual may fail or choose not to employ some aspects of the authority available to him, or, through manifest personal ineptitude, he may impoverish his position even as he attempts to be authoritative. On the other hand, he may, through personal preference and ability, succeed in getting superiors to delegate to him, and peers and subordinates to accept from him, greater authority than is strictly inherent in his office.

Boundaries

The division of labor defines boundaries, and the division of authority locates responsibility for regulating them. The concept of boundary is an aspect of open system theory, which treats organizations as systems whose survival requires continuous exchange of materials with the environment (Katz and Kahn; Miller and Rice; also cf. Silverman). Too permeable a boundary invites inundation, chaos, and disorganization, whereas an impermeable boundary becomes a barrier, causing death through entropy. (This last phrase is confusing as the use of the word "entropy" in open systems theory is assumed.)

The top management of an organization has responsibility both for the internal functioning of that system and for the regulation of its boundaries with the external environment. Authority for the internal operations can be largely delegated to subordinates. External boundary regulation is, however, much less delegatable; it must become the major task of top management if the system is to obtain the necessary inputs, to export the products of its labor, and to sustain a viable, self-determining relationship with its environment. An overly inward-oriented management negiects the boundary tasks and produces an encapsulated system that tends to become stagnant and incapable of growth --a common phenomenon in health and educational organizations.

In addition to boundaries separating the organization from its environment, there are also boundaries internal to the organization. These internal boundaries separate task systems from each other and, within the task system, separate distinct work groups. The regulation of internal boundaries is also a management task at the organizational level at which they occur; i.e., the leadership of a given subsystem must give major effort to boundary transactions with adjacent subsystems and with the authority to which it is responsible.

As noted, boundaries are a consequence of social structure. They are created through the division of labor -- the delineation of positions, work groups, and task systems. Similarly, a crucial aspect of the division of authority involves the designation of positions and groups as having responsibility for the regulation of various boundaries.

CULTURE

Culture is an aspect of social systems whether they are societies, communities, organizations, or work groups. We use the term culture to refer to central and relatively enduring values, assumptions, and beliefs which characterize a given social system and which are interrelated over time with the system’s social structure. Social structure tends to reflect underlying cultural values and helps to realize those values. Culture and social structure tend to be relatively congruent, but in a changing social system the fit will not be perfect. Over time, changes in the one are likely to produce changes in the other.

SOCIAL PROCESS

In our usage of the concept of social process, we intend two meanings. The first, more specific meaning is that commonly employed in the literature on group dynamics (Bion; Slater; Rioch). In this literature, the term group process is used to refer to the imagery, fantasies, and feelings, nonrational and irrational, which characterize collective life. These processes may interfere with the performance of group tasks, and to some extent (as Rice, 1969, has indicated) emanate from all those aspects of the person which are unused by his specific and limited role in the task work.

Our more general meaning of social process includes the former, yet more broadly encompasses mode and tempo of work, what in fact the group does. What methodology (or technology) does the group employ to accomplish its task and what is the tempo of the work -— continuous, low levels of activity over time (as in a small branch library) or alternating brief periods of intense activity and long periods of quiescence (a fire department)?

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude by restating and elaborating briefly on the two underlying theses of this study.

Thesis I: Social process in the work group is intimately related to its tasks, social structure, and culture.

Thesis II: The work group itself is strongly influenced by the tasks, structure, culture, and process of the organization.

As to theory, we take the view that a combined sociological and psychological perspective is required if we are to develop an adequate social psychology of work groups and organizations. Mental health professionals and investigators, operating from the model of the individual or the dyad, have usually focused upon personal feelings and interpersonal events in groups to the exclusion of task, culture, social structure, and process both within the small group and in its social environment. This approach immediately reduces group phenomena to an individual or dyadic level, rather than starting with the group as social fact requiring its own appropriate (sociopsychological) level of analysis and then proceeding to the individual. The result is a psychology of the individual or the pair within an unexplained group setting (i.e., unexplained because unexamined). This approach, however valuable in itself, does not provide or utilize a theory of groups, and the essential social facts to be explained are defined out of existence. It is our belief that a comprehensive theory of the work group cannot be limited to a single level of analysis but must conjointly utilize group-level constructs (such as task, culture, social structure, and process)(Note12) as well as constructs relating the group to its organizational and wider social context, on the one hand, and to its individual members, on the other.

REFERENCES

Bion, Wilfred R. Experiences in Groups; London, Tavistock Pubs., 1959.

Bucher, Rue. “Social Process and Power in a Medical School,” in Mayer N. Zald (Ed.), Power in Organizations; Nashville, Vanderbilt Univ. Press, 1970.

Durkheim, Emile. Suicide; Free Press, 1951.

Goffman, Erving. Asylums; Doubleday Anchor, 1961.

Hodgson, Richard C., Levinson, Daniel J., and Zaleznik, Abraham, Executive Role Constellation; Harvard Univ. Graduate School of Business Administration, 1965.

Inkeles, Alex, and Levinson, DanieL J. “The Personal System and the Sociocultural System in Large-Scale Organizations,” Sociometry (1963) 26:217-229

Katz, Daniel, and Kahn, Robert L. The Social Psychology of Organizations; Wiley, 1965.

Note1: Our conception of “work group” needs to be distinguished from that of Bion. For Bion, the work group is that aspect of group functioning which is not pervaded by basic assumption life. In his theory, the group is a work group only when it dedicates itself to the real work for which it has met. When the group is unable or unwilling to so dedicate itself, but instead acts on the basis of some irrational assumption (e.g., dependency, pairing, fight-flight) regarding its task, it is a “basic assumption” group. We, also, distinguish the extent to which a group devotes itself to task work as opposed to other concerns, including irrational ones. For us, however, a work group is an aspect of social reality and, as such, cannot be interpreted in and out of existence. It is always a work group no matter how the group's efforts are divided between the pursuit of its defined task and the pursuit of other aims.

Note3: Group dynamic theorists within the Tavistock tradition (e.g., Bion, Menzies) have tended to view organization and social structure as a defense against anxiety. Not only is such a reduction of complex social phenomena to individual-psychological constructs epistemologically problematic (cf. Durkheim), but also this specific interpretation is often untrue even within its own frame of reference. Using such a conceptualization, one often sees the reverse -- the development of disorganization or chaos in part as a defense against anxiety. Not infrequently (as in the present ward), a group or its leadership may allow and even foster ambiguity and confusion regarding the nature of the primary task in order to avoid what is anticipated to be sharp, focused, and painful conflict.

Note8: The distinction between position and role (Levinson, 1959) is important here -- position refers to structure, role to function. If one loses the idea of position and thinks exclusively in terms of role, as many social scientists do, then the examination of organization tends to overemphasize process, activity, and function and to overlook the structural base from which organizational activity proceeds. An occupant of one single position may, and probably will, carry out numerous functions deriving from his position; confusion ensues if one assumes that each function involves a separate location in organizational space.

Note7: There is no general consensus regarding the definition of the concept of authority. Often, the terms authority and power are used interchangeably. For us, there is an important difference between these two notions which, if obscured, limits the analysis of social systems. This difference rests upon the issue of legitimacy. Power denotes sheer capacity and implies nothing about the right to possess or use it. Whereas authority, by our definition, always involves some degree of power, power need not involve authority at all. Thus, anyone with a gun has power but, under the law, only the policeman ordinarily has the authority --the legitimate right-- to use one. Authority degenerates into power when its legitimate --legal or moral-- basis is eroded or overreached (cf. Schaar's “Legitimacy in the Modern State’). Katz and Kahn's treatment of authority (p. 220) as legitimate power inherent in positions within the organization is consistent with our meaning.

Note12: We do not regard this set of four constructs as exhaustive. In working toward a comprehensive analytical framework, we have started with these because we consider them of central importance. Among the other constructs that need to be taken into account in the study of groups and organizations are: material resources, technology, demography (i.e., the distribution of social and psychological characteristics such as sex, age, race, and work-relevant personality characteristics), and the like. An additional construct of importance here is that of “career”; that is, the differential participation of individuals in the work of the group and the organization is determined to varying degrees by considerations of career.

One page summary:

Newton_1973_workgroupInOrg1Pager.pdf

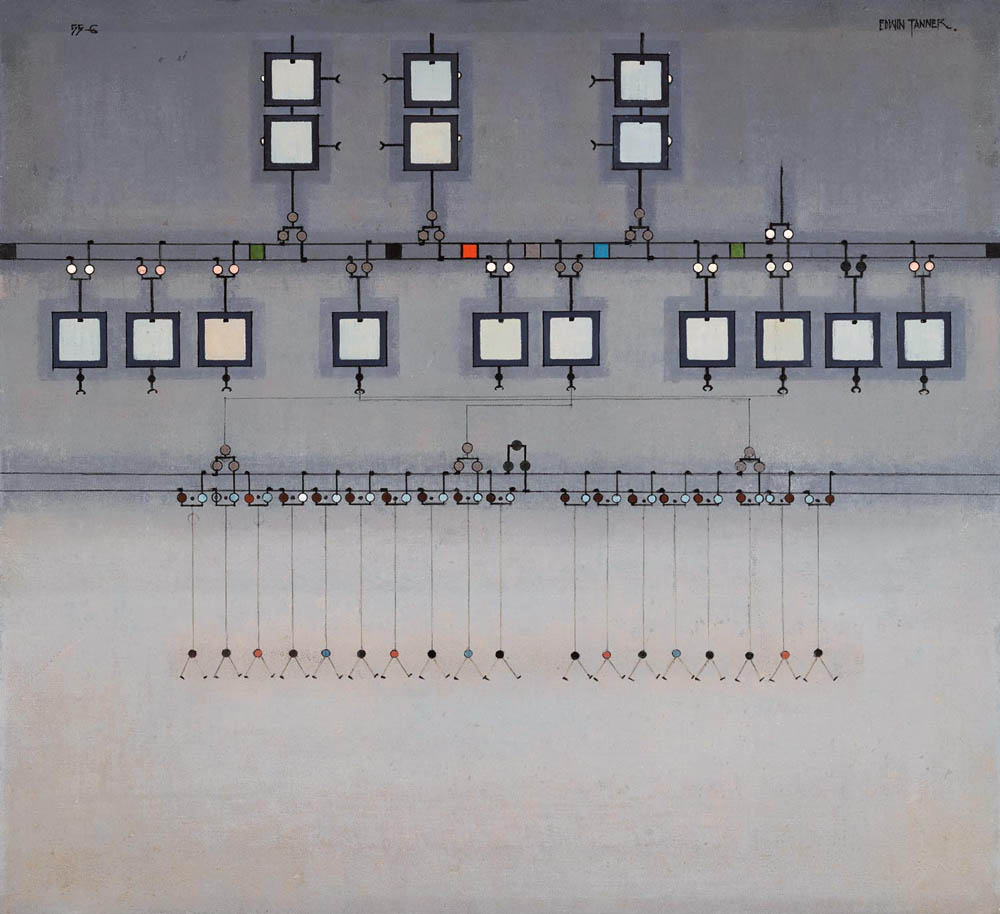

Edwin Tanner The Board of Directors

- oil on canvas on board - https://www.menziesartbrands.com/items/board-directors

(image and link added 2023-07-18)